ASTON SERVICE DORSET LTD

1904 NAPIER

FROM THE PEN OF IVAN FORSHAW

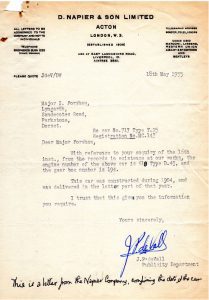

The following is an account written by Ivan Forshaw on how he went about finding and restoring the 1904 Napier: ‘In the years immediately following the war, I thought I would very much like to own an Edwardian or veteran car, a Napier of low horsepower, as I was much taken by the early history of this company. I was also friendly at the time with Roger Barker, who was a Napier enthusiast and who owned a 1909 30hp car, which had an excellent history and was a very nice car. Barker, being short of money, later exchanged it with Major Browell for a post First World War 40/50 Napier, £250 and 14 gallons of petrol, which was rationed at the time. This was a wonderful car but completely lacking the charms of an Edwardian. I went with Barker in the 1909 Napier to Elford's Engineering at Southbourne, where there was said to be a Napier in the yard. At that time, Elfords Engineering consisted of a number of rather dilapidated lock up garages. Elford senior was a dreadful and rude old man but the report about the Napier was correct. It was 1903 and a small one, later identified as a racing car driven by none other than Charles Jarrott. It was in a dreadful condition, having been outside for many years and covered in old oil drums and rubbish. Elford said he wanted £50 for it, a substantial sum in those days, and if we didn't want the car to get the hell off the property. In the meantime, I spoke to everyone I met who might have knowledge of an early car and the man who came to read the gas meter told me there was one in a private house garage in Upper Parkstone, owned by a medical doctor. This turned out to be a delightful little car, a Minerva of 1908 or 1909 with a 4-cylinder Knight sleeve valve engine, separate cylinders and cylinder heads. Unfortunately, the head of one of the cylinders was on the seat of the car and it was cracked. It seemed to me to be irreparable, but it wouldn't worry me now. The doctor wanted £50 for it, with a new tyre, and I didn't buy it. Perhaps it was a lucky escape, as sleeve valve engines are notoriously difficult to recondition. A scrap man told me of an early car at a farm in Stapleford near Salisbury. This was a pig farm and the stench was something else, owned by a family with the delightful name of Rhinel Tatt. It was in an old barn and old Mrs Rhinel Tatt had spent her honeymoon in it. It was a 1903 De Dion and I hadn't the heart to worry the old lady for it. When I called at the farm some years later, I found that the car had been taken by a person with no such scruples; they had badgered Mrs Rhinel Tatt and given her £30 for it in the absence of her sons, who were extremely angry about it. In 1956, I was in the General Post Office in Parkstone. Next in the queue was a man named Kent, to whom I had previously spoken of the problem. The brothers Kent were a couple of Dorset worthies who travelled around farms buying scrap machinery, completely likeable and honest men. Nothing had been found, but I could have a word with his brother outside in the lorry. His brother, Diver Kent, wondered if a small chain driven lorry would do. He couldn't remember exactly where it was except that it was in Upton, close by the road and in a low barn. If I found such a place the roof had collapsed and the car was inside. At an early opportunity I went to Upton and drove around until I found the old barn in Chapel Lane. Looking through the cracks in the door I saw the lorry inside; it was a magical moment!

CONTINUED

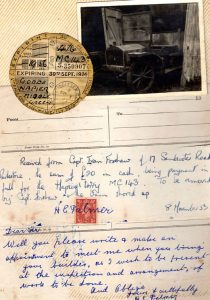

It was a Napier that had been converted to carrying goods in the First World War; this was considered to be the patriotic thing to do. I banged on the door and it was eventually opened by a very old man, 93 years of age. He was completely deaf, university educated and pleased to see me, salt of the earth. I asked if I could see the old car, he agreed and said he would be pleased to show me, but he wouldn't sell it. A number of scrap men had wanted to buy the car, but he wouldn't have it moved as it was pinned to the ground by the roof of the barn which had collapsed on top of the windscreen. If the car was moved, the barn would fall down. Subsequently I called in to see Mr Palmer whenever I was in the area and eventually he said that he would sell me the car but I would have to arrange for a builder to shore up the barn. When I asked him the price he said £20, as that is what he had been offered for it and I should have it for that.

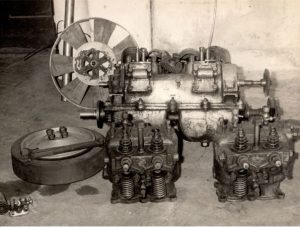

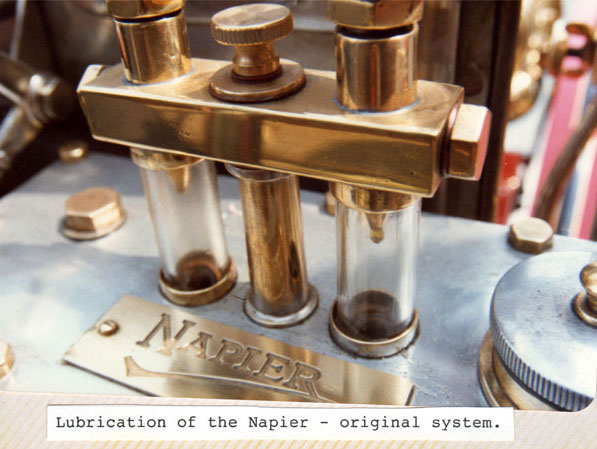

I saw Brooks, a sergeant, lately demobilised from the army who was renting buildings in Poole near some of these that I had at the time. Brooks went to Upton to look at the problem, was approved by Mr Palmer and later shored up the building and released the car, all for £1.10s.0d. I went to Trents and borrowed a trailer which was lying there. On the way to Upton, I was pursued by the owner of the trailer, who had seen and recognised it as it was being towed past his premises. He wasn't very pleased but soon mellowed and helped to load the Napier. The weather had free access to the barn and had kept the car in reasonable condition, apparently. I was later to find out the magnitude of what I had undertaken, and many times regretted what I had done. Dear old Mr Palmer went to London to collect the side lamps for the car, which I didn't know existed, and brought them to me. All he asked was to be taken to Christchurch to visit his brother when the car was finished. It was to be many years before this was possible, and long before that he was dead. On examination and dismantling of the engine this was found to be in really terrible condition, and I doubted whether it could ever be made to run again. The last time the car was used was in 1923 when it was driven down from London and I really do not know how it made such a journey. The crankcase was full of grease, which had been used as lubricant, the oil supply having failed or been non-existent. The engine had suffered a number of disasters in the past, probably as a result of lack of lubrication. It was clear that at various times at least two of the connecting rods had broken and had damaged the sump and the crankcase. The sump is aluminium and at some time, when the car was much younger, had been welded. The crankcase is also aluminium, and attempts had been made to weld it. The cylinder block had been replaced by another of slightly different type and the crankshaft was worn to such an extent that it was like a piece of bent wire. It was clear that if the engine was to be saved, much thought was necessary with many parts to be replaced or re-machined and all this was done over a long period with many frustrations and much research. I did the research and the placing of the work, some of the later proving ill advised. Veteran cars hadn't much value in those days and I wished to spend as little as possible. One of the major problems with the car was that it had no bodywork, simply a piece of wood on which to sit and a small platform behind so that it was a load carrier of sorts. The conversion was probably made at the time of the First World War, when transport was very scarce and it was considered the patriotic thing to make use of cars in this way. I originally intended to have a body made for it and Willie Reeves could have done this, but it would have been very difficult and expensive to make anything like the original.

Then in 1955, there was a note in the Veteran Car Club Gazette that a small builder had found a body in the loft of a coach house and thought it shouldn't be destroyed. I got a telephone number for the man and rang him at once. Following a discussion, it was clear that the body was a very early one and was probably just what was needed for the Napier and I told him that we should be along the following morning to see it. His name was Humphries and he was in a mountain village in Snowdonia. I telephoned Frank Dovey at Totten, who said that his nephew Frankie had a pickup which we could borrow. He would come with me and we should set off at five o'clock the following morning. I was at Frank's bungalow at that time and discovered that the pickup was still with Frankie, who was tucked up in bed when we got there. However, we eventually got away. The pickup was a pretty terrible vehicle and I soon had a bad migraine, a complaint from which I suffered torments over a long period of years. After finding our way along narrow lanes and steep hills, we eventually found Mr Humphries and were warmly received, given an excellent salad lunch and finally shown the body. I should have mentioned that it was by no means unusual for a car to have two bodies in the early years, an open body for the summer and a closed body for winter time. Bodies were very cheap as coachbuilders had been making them for many years, and they knew exactly what they were doing, but cars and chassis were very expensive. What happened was that the coach house was on an estate which had been bought by a company which supplied granite chippings for road making. The coach house had got in the way of mining operations and Mr Humphries had been engaged to demolish it. His men found the body in the roof and when he arrived on the scene were proposing to burn it, having stripped out part of the leatherwork and destroyed it. He stopped them feeling that someone would want the body. It was a rear entrance tonneau and exactly what the Napier needed. I asked him how much he wanted for it. He said £7.10s.0d. and I gave him double and got a remarkable bargain. It was many years before Will Reeves fitted the body to the chassis, it was originally a Daimler body but lent itself perfectly to the Napier. The wheels are of wood, hickory spokes and ash felloes. The felloe is the wooden section into which the outer ends of the spoke fits in. The woodwork was originally painted green. Nothing has been done to the wheels except cleaning off the paint, varnishing the wood and painting the rims black. The rims are screwed on to the felloes by long screws, the nuts of which should be tightened occasionally. Not too tight or the head of the screw will be pulled through the rim. There is danger that the ragged edge of the hole in the rim, or the screw head itself, may chafe the tube, and puncture it. A section of one felloe which was badly attacked by a woodworm was replaced by Will Reeves. The wheels are old and loose, they need periodic removal and total immersion in water to swell them up and they move and creak like I tend to! The carburettors originally fitted would have been of Napier's own manufacture and would have been governed. The carburettor fitted is a Krebs, probably from a Panhard Levassor. It is not governed and appears to be entirely satisfactory, though the mixture is a little rich and petrol consumption correspondingly heavy.

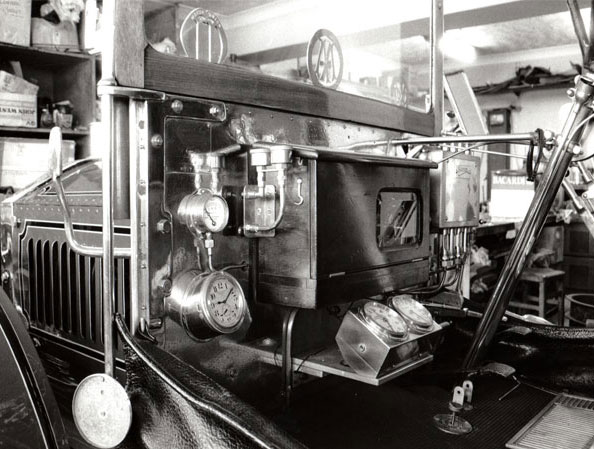

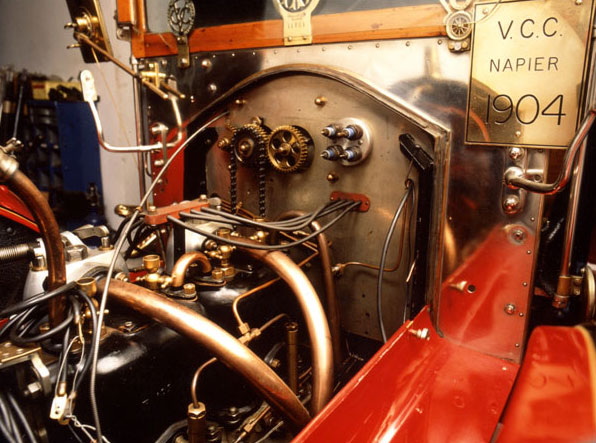

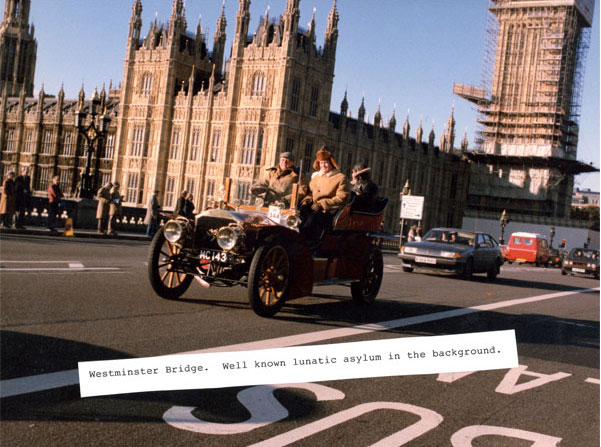

It might benefit from a choke tube of different size which George could make. He did in fact already machine one, but the variation was too great and the mixture was much too weak. We have the choke tube which George made, and this could be opened up a little to experiment. Additionally, we have made a simple manually operated choke lever for it, but although this is excellent for starting, it needs to be taken off soon after the engine starts. The choke lever simply seals off the entry to the carburettors, thus increasing the suction on the jet. There is a spare diaphragm in the toolbox. This is my own idea of what the arrangement and the parts should be like, and seems to be correct. The diaphragm, which I made originally for the carburettors, was found to be punctured and split in 1993, which almost certainly caused the maladies which the car suffered from in the London Brighton Run in 1992 and before. I fitted the new diaphragm which I had made and which was in the tool box. This seems to have cured the trouble but is probably not flexible enough. The true honeycomb radiator fitted when the chassis was bought was much larger in the holes. It was badly choked, and had been repaired in a number of places by blocking of the tubes so it was decided to replace it. I remembered that Alvis had used true honeycomb radiators long after other firms, even mounting them behind false radiator shells as late as 1934. I telephoned the spares department at Alvis and explained the predicament to the spares manager. He informed me they had two radiators of the kind left, brand new, which he said I could have for £5. On the following day, they delivered them to Westland at Yeovil, as they were supplying engines for the helicopters. Joe Pritchard, who was Westland’s resident solicitor at the time, took charge of them and delivered them to Longham. Altogether it was a remarkable stroke of luck. One of the new radiators was cut and fitted to the Napier shell by Jack Millward. It is entirely satisfactory. The water used should be distilled water, to avoid lime deposits in the honeycomb. The other new radiator is in stock, and would be suitable for the Napier if ever, which God forbid, it should ever be needed. It would also be suitable for some of the other cars, the Invicta and the OM, for example - if it should be needed. Make sure that anti-freeze mixture beyond recommended strength is put into the cooling system. The consequences of a frozen engine could be an absolute disaster. In total, it took 25 years to rebuild the Napier with its completion in 1982. From this point on, the car and Ivan took part in 12 London to Brighton Veteran Car Runs from 1982 to 1995 finishing on every occasion. Below are some of the remaining collection of photographs that cover the emergence of the Napier and its London to Brighton Days. The finished Napier emerging for the first time from its workshop at Aston Service Dorset. A detailed photo of the engine bay and the handcrafted inlet manifold pipes created by Technical Tubes. Ivan and George making final adjustments. George was forever tinkering and without his help the project would never have been finished. Ivan on the floor during the crucial hours before the start of the London to Brighton Run in Hyde Park. Richard Forshaw is looking into the engine bay. Janet and Simon are in the back. A cold October sunrise starts in Hyde Park with the cars all lined up. Ivan is in the passenger's seat, a position he hated, being unable to drive following numerous strokes and hip replacements. Always an enjoyable part of the trip driving through London with the early Sunday morning traffic. Ivan's observations regarding the building in the background remain extant today. Roger is in the front and Richard in the back. A watercolour painting by Rick Heuff, a Dutchman who was a customer of ours in the 1980s and owned a DB4GT. Arrival at Brighton with Roger driving and cousin John in the back, Toad of Toad Hall looking frozen and as though he had a thoroughly enjoyable trip! Another successful finish in Brighton with Ivan shaking the hand of Lord Montague and Roger chatting up a reporter! The Napier completed London to Brighton Veteran Car runs and was the most valued car in Ivan's collection, bringing him a lot of happiness and heartache. Despite having passed away in 2006, he still sits in the driving seat today.

Many men offered to help with the work and without such help the car could never have been completed in its present form or at all. The following is a list of the major contributors: Clifford Rees - Reconditioned the gearbox and differential. He also rebuilt the ignition box, all of which called for much skilled work. Derek Grossmark - Supplied the original ignition box in exchange for a Napier clock and some other small parts. Derek was a great Napier enthusiast and had three cars and a complete chassis at the time. Phil Rideout - Who out of the goodness of his heart made the main and big end bearings, and supplied the connecting rods at present in the engine. He also did other things; he largely machined the Commer crankshaft. The work on the engine could never have been done without Phil. No payment was made to him. Jessie - Who gave me the pistons, cylinder liners, engine valves and timing gears. John Morrow - Who elected to recondition the water pump and ended up making a completely new pump with improved seals and new driving wheel with leather discs. Brian Horwood - Who made the Napier script which is on the front of the radiator core. Frederick Prinee - The original chains were a mass of rust and Renolds declared them obsolete and refused to help. I appealed to Fred, who was at that time the owner of the Rotrax bicycle company, the makers of racing bicycles and Speedway frames. He was married to one of the Curry bicycle shop girls. Both were very substantial customers for chain and Renolds produced the chains for the Napier almost overnight and at very small cost. I ought to have asked for two sets! Fred also got the two front tyres from the Dunlop company. Cost £6.17s.6d each. The Alvis Car Company - Who supplied two honeycomb radiators at negligible cost. They were £5 each delivered to Westland, thence to us by the resident solicitor; we still have one. The following were either in our employment or were employed specially to do the work: George Williams - Who did an immense amount of work of every kind. Willie Reeves - Painted the body and chassis by hand, was also responsible for fitting the body and all instruments. K.A. Hughes - The sign writer, who lined out the wings and the bonnet. Jack Millward - Who fitted the Alvis honeycomb into the Napier shell. Hawkins - Who reset the road springs. Millbrook Paints - Who supplied the Valentines paint that we used. Rawhide - Who made good the missing leather in the body, rather rough. Raw working with David Watkins, it was a cheap job, leather from dismantled Lagonda cars was used and later dyed black with spirit dye.

INTERNATIONAL SHIPPING AVAILABLE

All payments should be made in UK Pounds Sterling (£) either by Cash, Cheque, Credit/Debit Card or Bank Transfer.